The Rabbi Who Believed

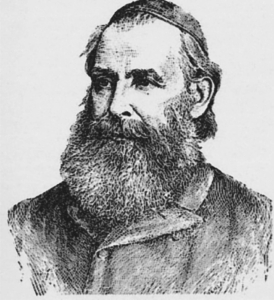

If Yeshua (Jesus) is the Messiah, why don’t our rabbis believe in Him? This is a thought-provoking question, but it begins with a faulty assumption. I want to share with you the story of an Orthodox rabbi who initially rejected the New Testament entirely but later came to embrace its core message—that Yeshua is indeed the Jewish Messiah. This is the story of Rabbi Isaac Lichtenstein.

Rabbi Isaac Lichtenstein’s early life

Rabbi Isaac Lichtenstein’s early life

Born on April 9, 1825, in Nikolsburg, Austrian Silesia, Rabbi Lichtenstein was raised in an Orthodox Jewish family. Growing up, he experienced bullying by Christian children. He recalled,

I remember still the stones which were thrown at us as we left the synagogue, and how, when bathing in the river, and powerless to prevent, we saw our clothes cast, with laughter and insult, into the water (A Jewish Mirror, 4).

In the mid-1850s, Lichtenstein became a rabbi in Tápiószele, Hungary. Early in his tenure, a local Jewish teacher showed him a New Testament that he was given. In response, Rabbi Lichtenstein rebuked the teacher for having such a book and confiscated it.

Blood Libel in Tiszaeszlár, Hungary

Lichtenstein’s experience of Christian antisemitism did not end in his youth. On April 1, 1882, a fourteen-year-old girl named Eszter Solymosi disappeared just days before Passover in Tiszaeszlár, Hungary. During the investigation, the Jewish community was falsely accused of blood libel—kidnapping the girl and murdering her in their synagogue to use her blood for their preparation of matzah. As the investigation unfolded, antisemitic propaganda spread across Hungary, inciting violence against Jewish people. In 1883, the court cleared the Jewish community of any wrongdoing when Eszter’s body was found, revealing no evidence of ritual murder.

During this turbulent time, one Jewish follower of Yeshua took a stand against the hatred by publishing a pamphlet using the words of Yeshua to demonstrate that no Christian should harbor animosity toward Jewish people. Rabbi Lichtenstein read the pamphlet, and in A Jewish Mirror, he wrote about how it impacted him:

Strangely enough, it was the horrible Tisza-Eszlar blood accusation which first drew me to read the New Testament. This trial brought from their lurking-places all the enemies of the Jews. . . . The frenzy was excessive, and among the ringleaders were many who used the name of Christ and His doctrine, as a cloak to cover their abominable doings. These wicked practices of men, wearing the name of Christ only to further their evil designs, aroused the indignation of true Christians, who with pen on fire, and warning voices, denounced the lying rage of the Anti-Semites. In articles written by the latter in defence of the Jews, I often met with passages where Christ was spoken of as He who brings joy to man, the Prince of Peace and the Redeemer; and His gospel was extolled as a message of love and life to all people. I was surprised, and scarcely trusting my eyes, I took a New Testament out of its hidden corner: a book which some forty years before I had in vexation taken from a Jewish teacher, and I began to turn over its leaves and to read (A Jewish Mirror, 4–5).

Finding the Messiah

When Rabbi Lichtenstein first read the New Testament, the words captivated him in a way he never expected. He wrote:

A sudden clearness, a light flashed through my soul; my eyes gazed astonished into the distance, as when through an electric shock the scales fall from the eyes of a blind man. It was to me as encouraging as health to one in sore sickness, as freedom to a prisoner in fetters; for I looked for thorns and gathered roses, I discovered pearls instead of pebbles—heavenly treasure; instead of hate, love; instead of vengeance, forgiveness; instead of bondage, freedom; instead of pride, humility; instead of enmity, reconciliation; instead of death, life—salvation, resurrection (Judaism and Christianity, 21–22).

Reading the New Testament was a transformative experience for Rabbi Lichtenstein, one that led him to see the text and its theology as Jewish, ultimately recognizing Yeshua as the Messiah. As a result, he immersed himself in a mikveh to signify his commitment to follow Yeshua.

For the first few years, Rabbi Lichtenstein kept his newfound faith private. He continued reading the New Testament as a sacred Jewish text. He embraced the teachings of Rabbi Yeshua and shared them with his congregation, though without citing his source. However, a couple of years later, on a Shabbat morning, Rabbi Lichtenstein publicly revealed to his congregation that his rabbinic source was Yeshua of Nazareth and that this rabbi was, in fact, the Messiah. Despite this revelation, many of his congregants continued to respect his authority as their rabbi and even followed his lead in accepting Yeshua as the Messiah.

Refusing to convert

Rabbi Lichtenstein adamantly refused to be baptized in a church, choosing instead to remain within Judaism and continue his role as a rabbi. Driven by his zeal for the Messiah, he published a pamphlet detailing his life story, which sparked opposition within the Jewish communities of Austria-Hungary. He was subsequently put on trial in Budapest before a rabbinic tribunal, led by the chief rabbi of Budapest, Rabbi Samuel Kohn. The tribunal demanded that Rabbi Lichtenstein retract his writings, and Rabbi Kohn urged him to step down from his position as rabbi and become a Christian, getting baptized in the church. However, Rabbi Lichtenstein firmly responded, “I have no intention of joining any church” (quoted in The Everlasting Jew, 18). He remained in his position as rabbi of his local synagogue, as his community refused to force him to step down from his post.

He continued to teach his congregation, and through his written work, he explained why Yeshua is the Messiah to Jewish communities while also defending Judaism to Christian communities. Rabbi Lichtenstein believed that if secular Jews embraced Yeshua as the Messiah, it could bring them closer to Judaism. He wrote:

From every line of the New Testament, from every word, the Jewish spirit streamed forth. . . . Every noble principle, every pure moral teaching, all the patriarchal virtues with which Israel was adorned in its prime (and is still, to some extent, adorned as the heir of the community of Jacob), I found in this book of books, refined and simplified. I found in it balm for every pain of the soul, comfort for every sorrow, healing for every moral wound—renewal of faith and resurrection to a new life, well-pleasing to God (quoted in The Everlasting Jew, 54).

Rabbi Isaac Lichtenstein is just one example of an influential Jewish rabbi, learned in Torah and Talmud, who embraced Yeshua as the Messiah and continued to live according to the way God calls His people to live—Jewish. In Rabbi Lichtenstein’s words, “Israel found its salvation in God, and the salvation of God is illuminated in the light of Messiah Yeshua. Therefore, Israel will never cease to be God’s people” (quoted in The Everlasting Jew, 66).

Public Domain

Public Domain